an analysis of pet food label usage. - dry food

by:IKE Food Machinery

2020-01-11

We use the 2008 health and diet survey to investigate the extent to which pet owners consult pet food labels.

We found that the use of pet food labels did not penetrate into shopping behavior as it did with the use of nutrition fact labels for human food purchases.

While we found no gender difference in the use of pet food labels in dog owners, women are less likely to consult labels in cat owners than men.

The data also shows that usage increases when there are at least three pets;

Compared with dog owners, pet food labels are rarely consulted by cat owners;

Use does not depend on the type of product purchased.

Since 1994, most packaged foods require nutrition fact labels and provide consumers with a variety of nutritional value information.

The latest data from the National Health and occupational health survey show that 42% of adults use this label in whole or most of their purchases on 2009/2010, up from 34%/2008 (Todd 2014).

In addition, Campos Doxey, Hammond (2011)

And Ollberding, Wolf, tento (2011)

Found that tag users prefer eating patterns to non-tag users.

Many of the benefits of standardized food labeling are also applicable to labeling of pet foods.

A goal of a pet food label, like a label for packaged food, is to help pet owners make smarter choices and thus provide better quality care for their pets (Michel et al. 2008).

Admit well-

The American Association of Animal Hospitals has established a correlation between proper nutrition and pet health, providing recommended pet nutrition guidelines with the aim of improving the life and quality of pets (

2010) American Association of Animal Hospitals.

In the United States, there are 95 million pet cats and 83 million pet dogs, and cats and dogs add up to nearly two to one more than the number of children under the age of 18 (

Pet supplies Association of America.

According to the American Pet Products Association, in 2013, pet supplies in the United States spent nearly $56 billion, and pet food alone spent nearly $23 billion.

In addition, pet spending has been growing at a rate of over 6 years of age.

The annualized rate since 1994 is 5% (

Association of American Pet Products 2014).

Although pets may have an impact on health and the pet food market is economically important, the use of pet food labels cannot be analyzed due to the lack of data.

2008 survey of healthy diet (HDS)

However, data on pet owners and their feeding habits were collected.

Using this data set, we investigate the extent to which dog and cat owners consult pet food labels for nutritional information when purchasing pet food for the first time.

We also compare consumer usage of pet food labels and usage of nutrition fact labels.

In addition, the 2008 HDS survey design allows an empirical analysis of the use of pet food labels based on the number and type of pets in possession.

The results presented here provide a baseline for comparing behavior with future results when other surveys interview pet owners about their use of pet food labels.

In order to distinguish the labels of food and pet food used for human consumption, we refer to the nutrition fact label as "food label" and the label on pet food as "Pet Food Label ".

In addition, "pet" refers to dogs and cats, and "pet food" refers to food for dogs and cats.

Finally, the "pet owner" is considered to refer to the self

According to 2008 HDS, this is the main buyer of pet food.

From a legal point of view, the history of pet food labeling, pet food is a subset of all products sold as animal food.

Animal food is regulated at both federal and state levels, and most state regulations exceed federal requirements.

Because each state has specific laws and regulations on animal food sold in the state, there are many different requirements for the labeling and composition of animal food. (1)

American Association of Feed Control Officials (AAFCO)

It is a state and federal association of officials involved in animal food regulation.

To facilitate uniform requirements for animal food in all regions of North America, AAFCO has developed a set of proposed laws and regulations (

Known as the AAFCO Model Act and the AAFCO model regulation)

The association recommends that states adopt (AAFCO 2014).

Although not every state has adopted the latest version of the AAFCO model regulations, there is a sufficient number of states, so that if the product complies with the current model regulations, the state will generally allow the sale of the product.

The AAFCO model regulations contain many of the same requirements as set out in federal regulations, including (1)

Describe the appropriate name of the product ,(2)

List in descending order of the weight of the ingredients used to manufacture the product ,(3)

The statement of netquantity in the package, and (4)

List of names and business locations of product manufacturers, distributors or Packers.

The current AAFCO model regulations also require calorie content to be indicated on all dog and cat foods by 2017.

AAFCO model regulations for pet foods require that most pet foods must guarantee minimum crude protein, minimum crude fat, maximum crude fiber and maximum moisture content.

Many manufacturers also list guarantees for additional nutrition, whether voluntary or supporting nutritional ingredient claims made elsewhere on the product label, such as omega-

3 fatty acids and ascorbic acid.

These guarantees give consumers the opportunity to compare products directly and make decisions based on nutrients.

The AAFCO model regulations also require a statement of adequate nutrition for most pet foods.

This statement explains the life stages and species of the product and how decisions can be made.

2008 HDS is managed by the FDA Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition.

These results came from a qualified response from a random selection of 2,584 American adults aged 18 or over who had residential calls.

The unit of observation is an individual in a family.

The study was approved under an exemption review by the FDA agency review committee.

HDS includes sampling weights that allow researchers to replicate the entire distribution of adult individuals with pets. (2)

Similar surveys have been used in the past to investigate the use of food labels (

Campos Doxey, Hammond 2011).

The purpose of this study is to extend this analysis to the use of pet food labels.

2008 what makes HDS unique is the use of pet food labels.

This section will identify the owners of dogs and cats and then ask about their pets and shopping habits.

The use of pet food labels is measured based on the following questions: "Now think about what happened when you first purchased apet food.

When you first look at pet food labels in a store or at home, if any, do you use thelabel to determine if the product meets the nutritional needs of your pet?

Will you say it often, sometimes, rarely or never? " (3)

Our analysis focuses on this issue as it asks about nutrition that can be obtained by looking at the guaranteed analysis, a statement of sufficient nutrition, and the direction of use of the product, which are included in the pet food label.

Limiting the analysis of major household shoppers is the standard practice of research on the use of food labels.

To reflect this, the respondents asked, "How many decisions have you made about the purchase of pet food in your home?

Would you say all of them, some of them, or none of them?

"We took a major pet food shopper as the person who answered the question.

1,049 respondents said they were the main buyers of pet food.

Of the families represented by these respondents, 528 had at least one dog, no cat, 298 had at least one cat, no dog, 223 of people have at least one dog and one cat. (4)

The results collected 2008 HDS in part to provide measurements of petfood label usage as a baseline for future comparisons.

Other pets besides exploring-

Related covariates for pet food labeling use, our analysis focuses on the relationship between food labeling and pet food labeling use.

Specifically, if the information provided by the two types of labels is of similar quality, the labeling usage rate between food and pet food labels may be similar, and people value the information equally.

On the contrary, if people pay more or less attention to the information of human food than pet food and/or the information provided on one label is more relevant than the other, possibility of use and application(5)

We also looked into the gender impact.

Generally speaking, it is easier for women to check food labels than men (

Blitzstein and Evans 2006

Campos Doxey, Hammond 2011;

2013 Stran and nol).

It is important to know if there are also gender differences when purchasing pet food in order to develop strategies on how to improve the use of labels.

Due to the lack of literature on the analysis of the use of pet food labels, the data are presented in the original form first.

Because the four classes used (

Often, sometimes, rarely, never)

Including each distribution, a chi-

Square tests with different distribution are almost always related to small p. value.

Therefore, although some

Give the value, Cross

The Tab analysis focuses on differences to varying degrees.

The logistic regression model for pet food labeling is then estimated. Cross-

Table 1 (a)

Depending on the extent to which food labels and pet food labels are used to obtain nutritional information when purchasing products for the first time, the overall weighted distribution of major shoppers with pets is provided.

According to 2008 of HDS data, 54% of pet food shoppers reported that they often use food labels 24.

8% report "sometimes" use, 9.

2% of reports use food labels "rarely" and 12% of reports use nutrition information labels "never.

This distribution of food labeling usage recorded in the literature (

2006. Blitstein and Evans;

Campos Doxey, Hammond 2011; Nayga, 1996).

In contrast, pet food labeling usage among these individuals is much lower than that of food labeling.

The percentage of pet owners who claim to use pet food labels for nutritional information is only 37. 5 (

Nearly 17 percent lower than buying food), and 26.

1% no pet food label is reported (

More than twice as big as food labels).

Comparing these two distribution methods, the use of pet food labels is basically lower than the use of food labels (p= 0. 0003). Table 1(b)

Report the distribution of pet food label usage by the number of pets owned.

These original percentages do not recognize clear patterns.

Having only one pet is associated with most use, either by "frequent" reactions or by combining "frequent" and "sometimes" responses.

However, when you have two pets, use less than if you have three or more pets. Table 1 (c)

Distribution of pet food label usage is provided by families with cats, dogs or two pets.

The use of pet food labels for pet owners is very different ---30.

7% of cat owners compared to 42.

Pet food labels are often used by 1% of dog owners.

Individuals with dogs and cats use pet food labels in a medium proportion (34. 9%).

However, it is unlikely that the owner of the dog and cat will only use the pet food label of the dog owner (p= 0. 0005)

Or just the cat owner (p= 0. 0170). Table 1 (d)

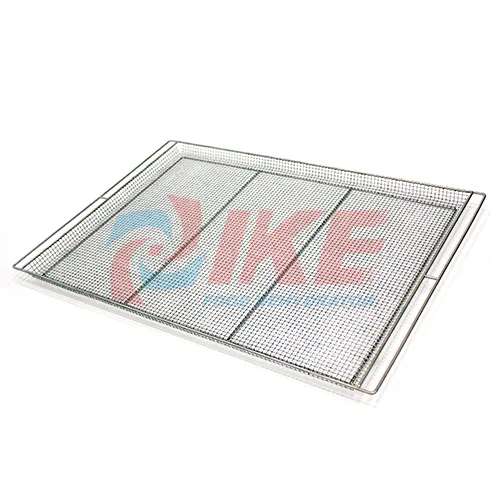

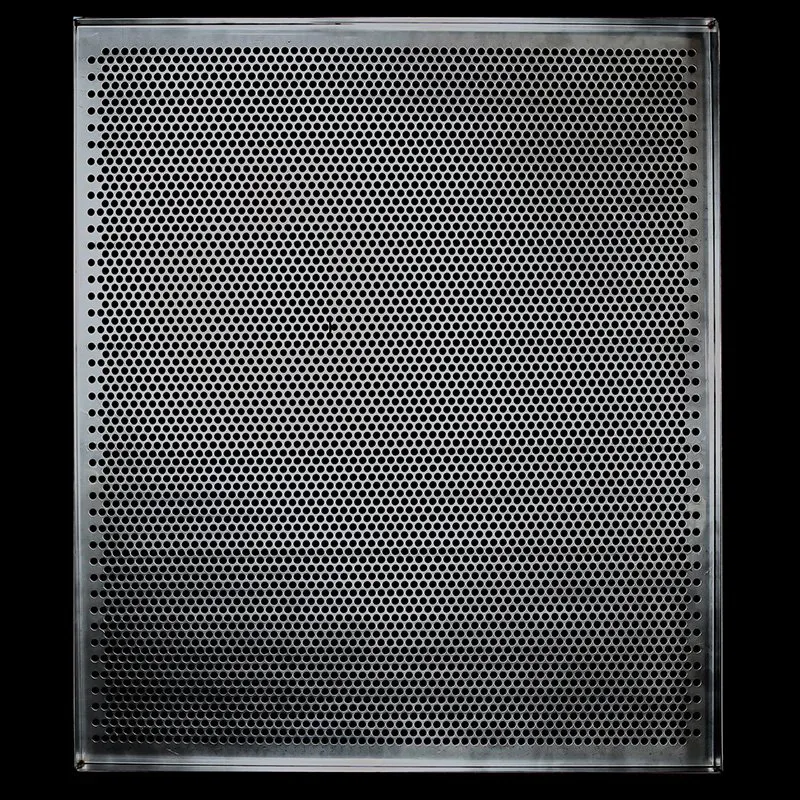

Distribution of pet food label usage according to the type of product purchased--

Dried food, canned food or snacks

It is important to note that 2008 HDS will not ask about pet food labeling for each type of purchase.

Instead, every pet owner is asked: did you feed your pet commercial dry food?

Do you eat canned business for your pet?

Do you eat commercial food for your pet?

Then, pet food label usage assignments were built for all pet owners who responded positively to specific categories.

As such, these reactions are not mutually exclusive by category, as one pet owner can be included in one, two or all three categories depending on the type of product they report to feed their pet.

While feeding dry pet food is more common than feeding commercial food, which is more common than feeding canned food, there are striking similarities in these three categories ---

About 38% of pet owners in each category report "frequent" use of pet food labels, about 27% report "sometimes" use of pet food labels, and about 25% of reports never use pet food labels.

There is no statistical evidence that the distribution of food species is different (

Campos, Doxey and hammond2010)

, There is no such difference between male and female pet owners.

It is not clear why this is the case.

This issue needs further study.

Like food labels, pet food labels provide consumers with important information about food nutrients, so increasing the use of pet food labels will have a positive impact on the health of pets.

According to 2008 HDS, 47% of pet owners report that they use veterinarians to get "a lot" of information about their "pet nutritional needs.

"Although veterinarians are the primary source of information, many pet owners may not be in contact with veterinarians more than once a year.

In addition, 2008 HDS also reported that pet owners often get information about their pet nutritional needs from books and magazines (15%)Internet (10%)

And advertising (8%).

Steps to expand the use of pet food labels (

Either by improving the label or educating the benefits of the pet owner label)

It can effectively improve the health of pets and enable consumers to make better shopping decisions from an economic point of view. DOI: 10. 1111/joca.

12076 American Association of animal hospitals. 2010.

AA ha nutrition assessment guidelines for dogs and cats.

Journal of the American Association of Animal Hospitals, 46 (July/August): 285-296.

Pet supplies Association of America2014. U. S.

Data and future prospects for the pet industry.

American Association of Feed Control Officials. 2014.

Demonstration regulations on pet food and special pet food under the Demonstration Act (136-147).

Oxford: Association of official publications of American Feed Control Corporation

Jonathan L. Bradsteinand Douglas W. Evans. 2006.

Use the nutrition fact group among adults who make a decision to buy household food.

Journal of Nutrition Education Behavior, 38 (6): 360-364. Bren, Linda. 2001.

Pet food: label on label.

FDA Consumer, 353): 26-31.

Campos, Sarah, Juliana Dorsey and David Hammond. 2011.

Nutrition Label on Pre-

Packaged food: system review.

14 years old (Public Health Nutrition)8): 1496-1506.

David. 1994.

Learn about pet food labels.

28-year-old FDA Consumer8): 10-15.

David. 2008.

Understand the regulations that affect pet food.

Companion Animal Medicine, 23 (3): 117-120.

Catherine E. Michelle, Kristina N.

Sarah K. WilloughbyAbood, AndreaJ.

Linda M. Faxti

Lisa N. Fleeman

Dorothy P Freeman

Lafram, Carcassonne de la Bauer, BronnerE.

Kemp and Janine R. Van Doren. 2008.

The attitude of pet owners to pet food and the management of cat litter dogs.

Journal of the American Veterinary Association, 233 (11): 1699-1703.

Rodolfo M. , Jr. 1996.

The determinants of consumer use of nutritional information on food packaging.

Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics, 28 (2): 303-312.

Nicholas J. , Randi L.

Wolf and Izabel Conto. 2011.

The use of American adult food labels and their relationship with dietary intake.

Journal of the American diet Association, 111 (5): S47-S51.

Kimberly. and Lindo L. Knol. 2013.

The determinants of the use of food labels vary by gender.

Journal of American Institute of Nutrition and nutrition, 113 (5): 673-679.

Jessica E. Todd2014.

Changes in diet patterns and diet quality at work

2005 Adult10, ERR-161. U. S.

Ministry of Agriculture, Department of Economic Research Services ,(January). (1. )See Bren (2001)and Dzanis (1994, 2008)

More information about the history and development of pet food labels. (2. )

In addition to the original reaction count, all the results in the article are reported after weighted data to replicate the distribution of pet owners over the age of 18 in the United States. (3. )

Telephone interview research on label use

Due to the inability to confirm the actual use of arespondent, deviations are reported.

Although this problem exists, it is not clear how biased the answer given over the phone will be.

Also, because 2008 of respondents in HDS were asked about the use of petfood labels in the same way as they were asked about their use of food labels, the results of the use of pet food labels should be comparable to the literature used for food labels. (4. )

The sample size may vary slightly due to lack of data.

Of the 1,049 respondents with pets, 1,031 had complete data. (5. )

While the same effort that led to an increase in food label usage over time could also lead to a similar increase in pet food label usage, it is also possible that pet owners do not use pet food labels as they do with food labels.

Unfortunately, if this is the case, the 2008 HDS survey will not allow us to determine if the low usage rate is due to the fact that shoppers do not know the pet food label and do not consider the pet food label useful, or do not value the pet's nutritional information as much as the pet considers nutritional information when purchasing groceries. (6. )The p-

Joint test values for all three coefficient sequences of the model [zero]1], [2], and [3]are 0. 6572, 0. 5272, and 0.

9117 respectively. (7. )

This result on female cat owners is not reliable on how to measure the use of pet food labels.

All previous results of the discussion insist that the use of pet food labels is defined by grouping "frequent" and "sometimes" usage (

As shown in Table 3

Alternatively, if the use is more strictly defined as "Pet food labels are used frequently ".

"However, there is no gender difference in the use of pet food labels when using this more stringent definition.

When the use is defined as the use of pet food labels "often" tearEstimation model]2]

Table 3-0.

193 The coefficient of "female shoppers" is estimated to be statistically insignificant --0. 061. Robert J. Lemke (

@ Mr. Lakeforest lemak. edu)

Samuel Wallin, Professor of Economics (

Valcin in Lake Forest. edu)

He is a student at Lake Forest College. Charlotte E. Conway (charlotte. conway@fda. hhs. gov)

He is an animal scientist and William. Burkholder(william. burkholder@fda. hhs. gov)

It is a veterinary officer at the FDA veterinary center and a board-certified veterinary nutritionist. Amy M. Lando (Amy. Lando@fda. hhs. gov)

Is a consumer science expert at the FDA Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition.

The Richter scholar guidance program at Lake Forest College provides financial support for Lemke and Vasin.

All the mistakes are our own.

Custom message